Ban Cash >>>End To Everything Bubble

Looks Like Graham Summers Sees The Future Of The Monetary System

01/24/2018 – The Roundtable Insight: Graham Summers On The Everything Bubble

TRANSCRIPT OF VIDEO

FRA: Hi welcome to FRA’s Roundtable Insight .. Today we have Graham Summers. He’s current president and chief market strategist of Phoenix Capital Research, a global investment research firm located in Washington D.C. He’s a graduate MBA of Duke University. With over 15 years’ experience in business strategy investment research, global consulting and business development.

Welcome, Graham.

Graham Summers: Hi Richard it’s nice to be here.

FRA: Great having you on the show. Today we’d like to focus on your new book The Everything Bubble: The Endgame For Central Bank Policy and you got the book divided into two parts; how we got here and what is to come. So maybe we can base the discussion on that if you want to give us some insight into how we got here.

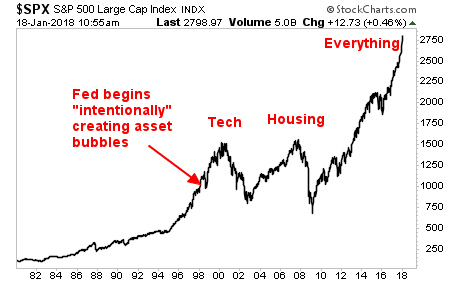

Graham Summers: Sure absolutely. So the idea for the book hit me when I saw that central banks, particularly the Federal Reserve in the United States, because I’m based in the US and most of my clients are, so my focus tends to be on that financial system. But I noticed that central banks were intentionally creating a bubble in sovereign bonds, which in the US we call them treasuries and they did this in response to the 2008 crisis. When I saw that happening it was cause for severe concern because in our current way that our financial system is set up, these bonds are actually the bedrock of the financial system. They’re the most senior asset class that there is. And if you look at what’s happened the last 20 years, we’ve had this kind of period of serial bubbles. In the late 90s, we had a bubble in technology stocks. They called that the “tech bubble”. Then when that burst, the Federal Reserve intentionally created a bubble in housing that was the housing bubble which led to the Great Financial Crisis of ’08. The significance of that is that housing is a more senior asset class than stocks. Then when the Great Financial Crisis hit in ’08, they dealt with that by intentionally creating a bubble in bond. So this is what actually gave me the idea for the title of the book The Everything Bubble because if you create a bubble in the interest rate against which all risk assets are measured, you’re going to end up creating a bubble in everything. It’s like raising the tide of the ocean, every ship going to rise as well. So I started writing the book and essentially what I quickly realized was that in trying to describe these things most people were probably not going to have a good idea of what I was talking about. And they were also probably going to ask why are things this way. So I divided the book into two parts: how we got here and what’s to come. The first half how we got here essentially started with the creation of a Federal Reserve and runs all the way up to about 2016. And I wrote with using a very simple plain language because a personal pet peeve of mine is that finances intentionally kept kind of opaque and confusing because I think it’s meant to keep most people ignorant of how the system actually works. So my goal was to write at least a hundred pages that anybody in the world could read and would instantly be brought up to speed on how did the United States financial system come into being. Why was the Fed created? How does the Fed work? You know, how did we get off the gold standard? And eventually leading up to the current era which is: how did we get into this mess? Where basically every 10 years we’re having these massive financial crises. And why is that the Central Banks are getting away with policies that really are completely insane and which none of us voted for?

I guess that answers your question.

FRA: Yeah that’s interesting. So can you walk us through in terms of the era of serial bubbles beginning, the Fed crossing the financial Rubicon, and leading up to the Everything Bubble?

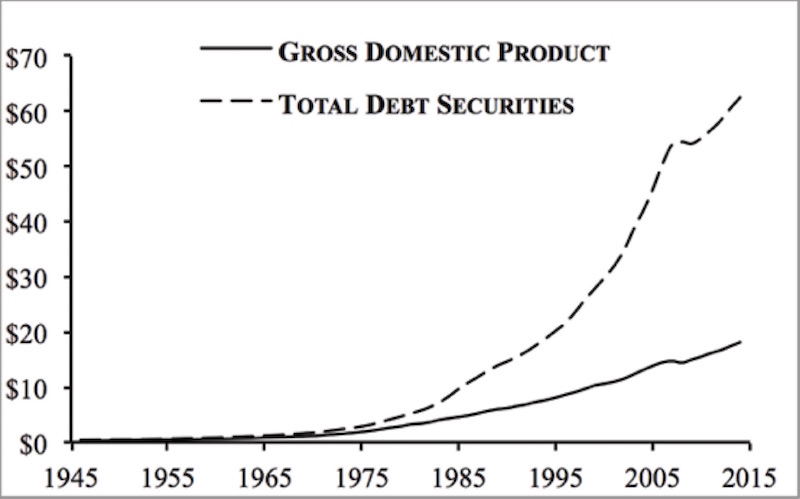

Graham Summers: Sure I’d be happy to. The easiest thing to do by the way is to just if you really want to know about the things, buy the book. It is on Amazon I think they’re running a 10 percent discount. So the stuff you’re interested in, by all means, check the book out. But the kind of the bullet point way I’d run through this would be when the U.S. completely severed from the gold standard in 1971. It did two things. Number one is: it opened the door to endless money printing because up until that point if the Fed chose to print a ton of currency, central banks and foreign governments could still convert their dollars into gold if they wanted to via the Fed. So up until that point while the Gold Standard had technically been ended for most of us in 1933 by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, it wasn’t until 1971 that the gold standard really was rendered moot for everyone including central banks. So when that happened, suddenly the US Federal Reserve and the United States would be paying any and all debt using U.S. dollars. And of course, these are U.S. dollars that the Federal Reserve can print. So what happened at that time was you see a sudden ballooning of debt relative to the actual economy in the United States.

And there’s a chart in the book which shows basically GDP, which is the gross domestic product, which is the annual economic output of the U.S. and the second line is the total debt securities and the financial system. And what do you see in that chart is that starting around in the 70s these two lines are pretty close together, but after 1971 when the world was removed from the gold standard, the trajectory of the deadline was almost parabolic and just keep going up and up and up. Meanwhile, GDP continues kind of in a linear fashion growing. This was that suddenly the system flooded with debt because the debt is paid for by dollars which the Fed can print at any time so there’s no limit to any of that. What this did was it got us to a point where in the late 90’s the amount of debt relative to the economy was so massive that if ever there was a serious period of debt deflation, which is basically a time in which debt prices are falling which means they’re starting to go insolvent, which means that people are going bankrupt. You’re going to have to restructure debt. As soon as that started to happen the Federal Reserve would panic and flood the system with liquidity because the dirty secret for central bankers is that the thing they fear most is debt deflation. When debt deflation hit, which is when debt falls in value, which means its yield goes up. It means it becomes more and more expensive to issue debt. And if most governments in the world have been financing their budgets with debt, the minute the debt deflation hit, that’s essentially the bond market saying, “hold on now it’s going to cost you a lot more if you want to continue financing your budget”. So this is always the focal point for the Federal Reserve, which is why starting in the late 90s. The Fed switched to a policy of intentionally creating asset bubbles because the alternative would be to let the financial system reset by allowing the debt to clear. Nobody is going to go for that because first of all, it is political and career suicide and second of all it’s the complete systemic reset. So Greenspan then Bernanke and ultimately Yellen all engaged in the same policy, which would then create asset bubble and any time that the asset bubble burst and a crisis hit, it will simply flood the system with more money and create another bubble.

FRA: This is quite interesting also in light of the cryptocurrency developments you mentioned the central bank power of printing money, fiat money, this whole monopoly power. Do you think that governments will give up this monopoly power to private-based cryptocurrencies? That this would be something that would not allow them to print money at will.

Graham Summers: No, they won’t endorse that in any way. Cryptocurrency is the result of two things. One is the fact that central banks are basically trashing their currencies by printing so much money and money capital flows to where it’s treated well. And if your alternatives are Swiss Francs or Euros or dollars all of which are being printed by hundreds of billion, you’re going to seek something else. So I view cryptocurrency as the natural kind of reaction to the system being set up the way it is essentially an individual saying well I want to get out of there somehow and I’m going to create an alternative. The secondary effect is capital flight from China, which is that hundreds of billions of dollars are fleeing China and they’re using Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies to get the money out. We know that 80 percent of the trading volume of Bitcoin is actually in China, but that’s sort of a topic for another time. But no to answer your question the Fed will never endorse cryptocurrencies. What the Fed will most likely do is try to create its own. And we know from an interview that the New York Fed President William Dudley gave back in November that the Fed has actually been examining that and looking into creating their own alternative to Bitcoin and the Fed would love that. Because if the Fed could somehow get the system to go completely electronic meaning physical cash no longer exists, it would allow the regulators to monitor every single transaction that occurs. And it would also remove the systemic risk of cash because physical cash only represents about 1 percent of the actual wealth within the system. And another dirty secret is that if enough people ever went to the bank and demanded their money in physical cash the whole system would blow up, the money is just not there. You know 99 percent of the so-called wealth is just electrons stored on bank servers and none of the banks actually have the money on hand, which is why a big goal for central banks is to get rid of physical cash in the next 10 years or so.

FRA: Yes, I agree with you fully and that gets us into your other section on what is to come. So you do talk about that the war on cash and also I would say it ties into negative interest rate policy because with the abolishing of cash it would allow central banks to more easily implement monetary policy especially if it goes into negative interest rates. Would you agree?

Graham Summers: Absolutely. So if you look at what I call the period of serial bubbles which is the late 90s till today. The Fed’s response to every crisis has been more and more extraordinary. When tech stocks blew up and we had the tech crash, Alan Greenspan kept interest rates down at 1 percent and he kept them there for like three years more than he should have which is what created the bubble in housing. Because if the rate of interest held by the Federal Reserve is lower than the growth rate of economic activity, money is essentially free because you can borrow money at the interest rate investing almost anything in the economy and you’re going to pocket the spread. So that was how the Fed dealt with the tech crash. Then the housing crash happened and the Fed cut interest rates to actual zero, keep them there for 7 years and does something like 3 trillion dollars in quantitative easing, which is basically printing money and then using that new money to buy assets from the banks which is the kind of backdoor bailout essentially the Fed doing a kind of cash for trash for the Wall Street banks. So that’s what happened last time around and we now have a bubble in sovereign bond and those are the most senior asset class in the financial system. The natural logical conclusion would be that when this bubble burst we’re going to have to see even more extreme policies. And the Fed has already hinted that in research papers and in speeches what those policies would be. They would most likely be negative interest rates meaning the rate of interest the bankers and the Fed is charging on the system is negative three or maybe even negative five. We’d also have that combined with nuclear levels of quantitative easing, so quantitative easing of like 100 billion or more per month. And then at the same time they try to ban cash. The way all of this would work is implement negative interest rate. Well that makes it difficult to sit on cash, so you banned cash so that people can get their money out of the banking system and in faith because of banks trying to charge you 3 percent on your deposit. Well heck just put your money in a safe. You don’t have to pay that interest anymore. So the Fed’s going to want to close the loophole that physical cash present. Than nuclear quantitative easing, the goal here is to just buy as much debt as possible to try and stop the debt bubble from deflating in an attempt to reflate it. And then the final policy will probably be some combination of wealth taxes, bail in and capital grab. Then what basically the way I would describe this is think of it this way, if the problem is that there’s too much debt, your goal is going to be to get as much capital as possible. So any money that’s lying around whether it’s in physical cash or in say, a payroll check you haven’t cashed for a couple of years and you just forgot about it. Or perhaps a CD, a certificate deposit, lying around or even savings deposit that you have in a bank. Government regulators are going to want to get their hands on it, much of that is possible because at the end of the day the issue is there’s too much debt. Most of the large entities in the system are financially insolvent as soon as interest rate normalized. And so they’re going to try and seize as much capital as they can.

FRA: Yeah exactly. And the NIRP, the negative interest rate policy, could also be in light of inflation or rising inflation if you have real interest rates as being negative, so nominal minus interest equals real. What exactly do you see playing out in terms of negative nominal interest rates or just negative real interest rates with rising inflation?

Graham Summers: I think we’ll see actual negative interest rates meaning the interest rate is in the negative like negative three in nominal terms. If you look at the history of the Federal Reserve, typically, when they react to a crisis or a recession on average they cut interest rates about five percent from their prior peak. Which following that line, if interest rates are three percent or the next crisis hit, they’re going to cut them five percent. That’s going to get you to negative two. If interest rates are around one, that gets you down to negative four, so this is how it’s been every time for the last 70 years. So I do think we’ll see nominal interest rates. We have them in Japan, we have them in Europe. Both cases demonstrated that nobody who implements them actually gets kicked out of office which is the ultimate fear for politicians and the central banking class. So no one gets kicked out of office for doing it and for whatever reason the system goes along with it. The reason the system goes along with it is if your option is to pay a little bit of money in NIRP and I end up losing that money, but the bond bubble stays intact and the system continues to function. Versus I don’t pay NIRP, I dump my bond. The bond bubble blows up and everything goes systemic reset, you’re obviously going to choose the first one. So this is why Central Banks have been allowed to get away with policies that just defy logic. If the alternative is everything blows up you’re going to go along with it no matter what. And we saw this with NIRP in Europe, we saw with bail-ins, which is when your savings deposits are actually raided by the bank and used to keep the bank afloat. We saw that in Cyprus, they got away with it there. So, currently there’s not really any indication that there’s going to be enough societal unrest to actually stop central banks from doing that. So, obviously they’re going to do it.

FRA: And do you see the Everything Bubble as bursting at some point or will it be more off of a situation where these measures as you mention the financial repression of war on cash, bank bail-ins, and wealth taxes. Do you see those measures as ongoing within Everything Bubble continuing to expand?

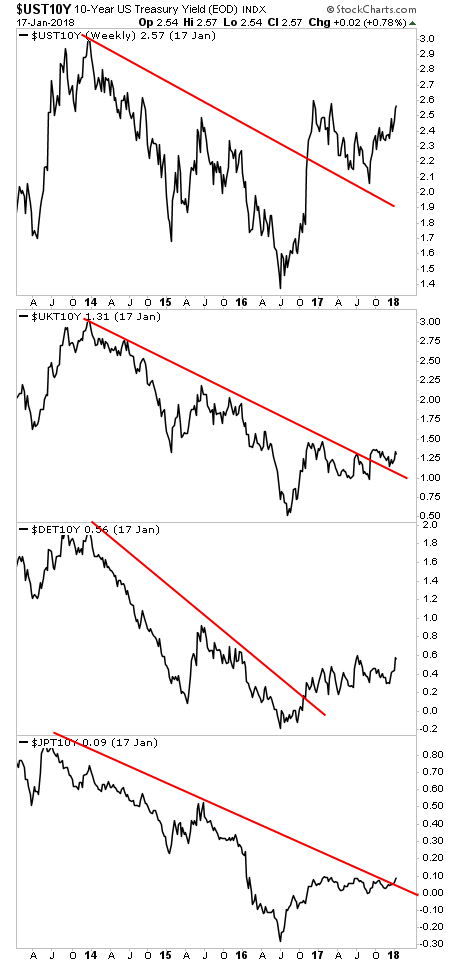

Graham Summers: Yes. The second option, they’re continuing. It’s very complicated to answer that because if you have an Everything Bubble, you’re going to have small asset classes blowing up. The real question is what happens when the sovereign bond markets finally blow up. That’s when you get the actual sort of systemic crisis. So if you look at the debt market as different sectors. For instance, the subprime auto loan sector is currently under a lot of duress. So there are little areas in the economy that are already blowing up here and there. My view currently and what we’ve been telling our clients is that we think central banks are going to have to taper and withdraw liquidity this year because inflation is beginning to threaten the bond bubble. What I mean by that, is bonds trade based on inflation. Inflation is rising, and then bond yields will rise to match it. If bond yields rise, then bond prices fall. If bond prices fall enough, then you start to have a debt deflationary collapse. And while we’re starting to see is that the bond yields on the German, Japanese and United States government bonds are beginning to all rise. So the bond market, the sovereign bond market, is beginning to react to a fear of inflation. Now if central banks have a choice: pool liquidity and let stocks drop or continue with the liquidity, let the inflation genie out of the bottle and blow up the bond. They’re going to choose number one. So my current view is that in the near future like the next six months, you’re going to see a lot of central banks pulling back and getting more hawkish and they’re going to let stocks correct in some way to try and keep the Everything Bubble, the bond bubble, intact. Whether or not that works, I don’t know because once inflation starts rising it’s very hard to get it under control.

So that’s where we are right now, but actually timing the Everything Bubble bursting and thing on this day it’s going to blow up. That is impossible. You know what you can do is you can look at what’s developing in the market. That’s what I do in my financial newsletters and assess where we are in things. Currently, we’re starting to get into dangerous territory. And what matters now is to see how central banks react to it. You know if they pull back and get hawkish, they probably can get away with keeping the show going a little longer, but if they just keep printing money, particularly the ECB and the Bank of Japan, and funnelling it into the financial system by tens of billions of dollars. Inflation’s really going to become a major problem and that’s going to really crash the bond market.

So that’s where we are right now.

FRA: What about longer term. How you see that playing out?

Graham Summers: Well longer term at some point the whole thing is going to blow up just like it did in ’08. Timing exactly how that happens, you’re going to have to look for key things. You know what triggered ’08 was the underlying asset class, which the bubble was based on, in that case housing, those prices peaked and began to drop. So that started to happen with sovereign bonds recently. The question is: does that continue to happen? And then you start to see the derivatives markets and the credit markets locking up. Because if you look at ’08, the crisis, in terms of the progression you had housing peak in ’06. Then you had some of the investment funds that were investing in subprime mortgages, which is the riskiest component of the bubble blowing up that was in ’07. In ’08, the derivatives and credit markets were locked up that’s how got the great financial crisis. So if you view that as a kind of template for where we are now. The underlying asset class, in this case sovereign bonds, has peaked and is beginning to turn. The question is: Does it continue to do that and then we start to see investment funds, bond funds, and then the credit markets blow up? We’ve yet to see that and that’s the key thing I’m looking for right now. If that starts to happen that means we’re in late 2007 area of the timing of the next crisis, which would mean the next one would be insane in the next 12 18 months. But again these are the things we’re all looking for. I haven’t seen them yet. There are no definitive signs that the crisis is beginning right now. The only definitive thing is we’re seeing that the bond yields are rising and this is going to start to concern central bankers very shortly.

FRA: Could the sovereign bond debt crisis be catalyzed through Europe? If we look at Europe, what’s happening in terms of a withdrawal of some of the quantitative easing from 60 billion Euro per month to 30 billion Euro per month — Could the actual crisis come out of Europe rather than the US or Japan?

Graham Summers: It could come out of Europe for sure, it could also come out of China. In terms of Europe, the issue there is that you’ve got a lot of distinct countries with their own individual central banks none of which can print the currency anymore. The only bank that can print Euros is the European Central Bank, which is overarching all of the European Union. You know Germany has its own central bank, so does Italy, but they can’t go and print Euros. That’s what actually led to the crisis with Greece and these other countries. Well, let me back up what led to the crisis for those countries have they had too much debt relative to tax receipts. The reason why those crises actually accelerated and became systemic in nature was their central bank could not print currency or engage in bailouts directly to try and prop the system up. They had to go to the European Union and if you go the European Union then you have issues where countries like Germany and France are saying, well why are we bailing you out when we don’t have a crisis ourselves? So Europe is a kind of a weird case of mutually assured destruction. You know on the one hand if a country leaves the Eurozone, and not like Britain did but like an actual country that’s located directly in it like Italy or France, then the whole thing blows up because suddenly the credit markets go because at that point the credit rating for the European Union is different. You start seeing interest rates rising and that will render these countries insolvent. So, Europe is kind of strange case where they’ve sort of cobbled this thing along. A lot longer actually than I thought they would. I thought they were actually a serious risk of going under in 2012-2013, but again it comes back to that original issue, which is if the option is: Do I go along with this insane policy and assist the main is kept the float or do I reject it and the system blows up? Everybody in a position of power whether it’s a politician, large-scale financial firms, and the central banks is going to go number one. But absolutely if you want to look at countries that are at risk of blowing up Europe would be top of the list along with Japan and China. The U.S., while its debt situation is also catastrophic, has the benefit of having the reserve currency of the world and a more diverse and liquid economy. The way I like to put it is the U.S. is kind of the least dirty shirt in the bunch, but the reality is every single one of them is in serious trouble the minute rates normalize and when that happens then it’s anyone’s guess exactly how it goes down.

FRA: And finally, how do investors invest in this environment? How can they protect themselves in what you’re saying is likely to happen just from a generic asset classes point of view?

Graham Summers: You know everyone’s risk profile is different. If you’re looking for sort of active investment advice and sort of being steered through the financial markets on a week by week basis I write a financial product called “Private Wealth Advisory”. That’s the sort of actively involved we’re buying commodities now or selling bonds now kind of thing. That’s more for people who are actively in the market, who want to have their capital directed in a way that they’re going to continue to profit no matter what happens. If you’re someone who’s more just concerned, what do I do in the next crisis hits, you know, how do I prepare? I’m not really looking to invest actively. The best bet is probably to invest in actual hard assets, things like gold, real estate things that you actually can touch with your hand. Things that actually in the case of hard assets real estate produces some cash flows as there are benefits there. But really think of it this way if the whole world is based on paper debt, then actually owning something outright particularly something that has some sort of financial stability and a less volatile price movement that’s probably going to be one of the safer places probably to be. Does that mean that if you put all your money in real estate you’re not going to lose anything when the crisis hit? Absolutely not. Everything will get hit. The question is: how do I preserve my capital in the way that it’s hit less and I emerge from the situation with as much of my wealth intact? The only real way to go about that would be somewhere in the hard asset class is: gold, precious metals, real estate, businesses that have operating cash flow, and stable demand things. I mean there’s a big reason why Warren Buffett’s been loading up on things like Kraft and other businesses that no matter what happens, you know people will continue to eat cheese or continue to drink beer, and Budweiser awhile back. And that’s sort of the way I’d look at it that way. So it really depends on your risk profile I can’t say hey everyone go do X because everyone has a different risk profile. Everyone has a different interest, but the reality is if the big picture way of looking at things is hey there’s too much debt then central banks are going to be forced to devalue their currency to finance that that you’re probably going to want your money in something of tangible value as opposed to something based on that currency which is going to be devaluing.

FRA: Wow that’s great insight, Graham. Thank you very much for being on the Program Show. We will post a link and information on the book on the website as well. And do have a website that our listeners can learn more about your work.

Graham Summers: Sure we have two websites. One is phoenixcapitalresearch.com. That’s our website for our products where if you’re looking to be actively involved in the market you want someone actually directing you to buy and sell a different thing to tell you what symbols to buy and what price to pay. That’s where you want to go. If you’re looking just to get sort of more familiar with our work. You can do two things one is you can buy the book “The Everything Bubble: The Endgame For Central Bank Policy” on Amazon right now. Or you can go to our free e-letter. That’s called gainspainscapital.com. That’s totally free. I send out a daily briefing on what’s happening in the market and assessing some of the big picture things that are going on in the system. And finally we’re on Twitter gainspainscapital, but the Twitter handle is the @GainsPainsCapit ending with the T. And you can find us on Twitter and I am on there most days commenting on what’s happening in the world.

So those are a lot of different ways you can get a hold of us.

FRA: Also we will interweave some slides that you’ll send within the body of the transcript of this podcast on our website as well. That would be great.

Graham Summers: I’m sure they’ve done based on the conversation. I’ve got a couple of charts in mind that should help illustrate some of the things we talked about.

FRA: Thank you very much, Graham, for being on the show.

Graham Summers: Thank you. My pleasure, Richard.

“The Everything Bubble: The Endgame For Central Bank Policy” on Amazon right now. <https://www.amazon.com/Everything-Bubble-Endgame-Central-Policy/dp/197463406X>;

Transcript submitted by Boheira Manochehrzadeh.<bmanoche@ryerson.ca> and Daniel Valentin

Disclaimer: The views or opinions expressed in this blog post may or may not be representative of the views or opinions of the Financial Repression Authority.